Concept and photographic direction PAUL KOOIKER

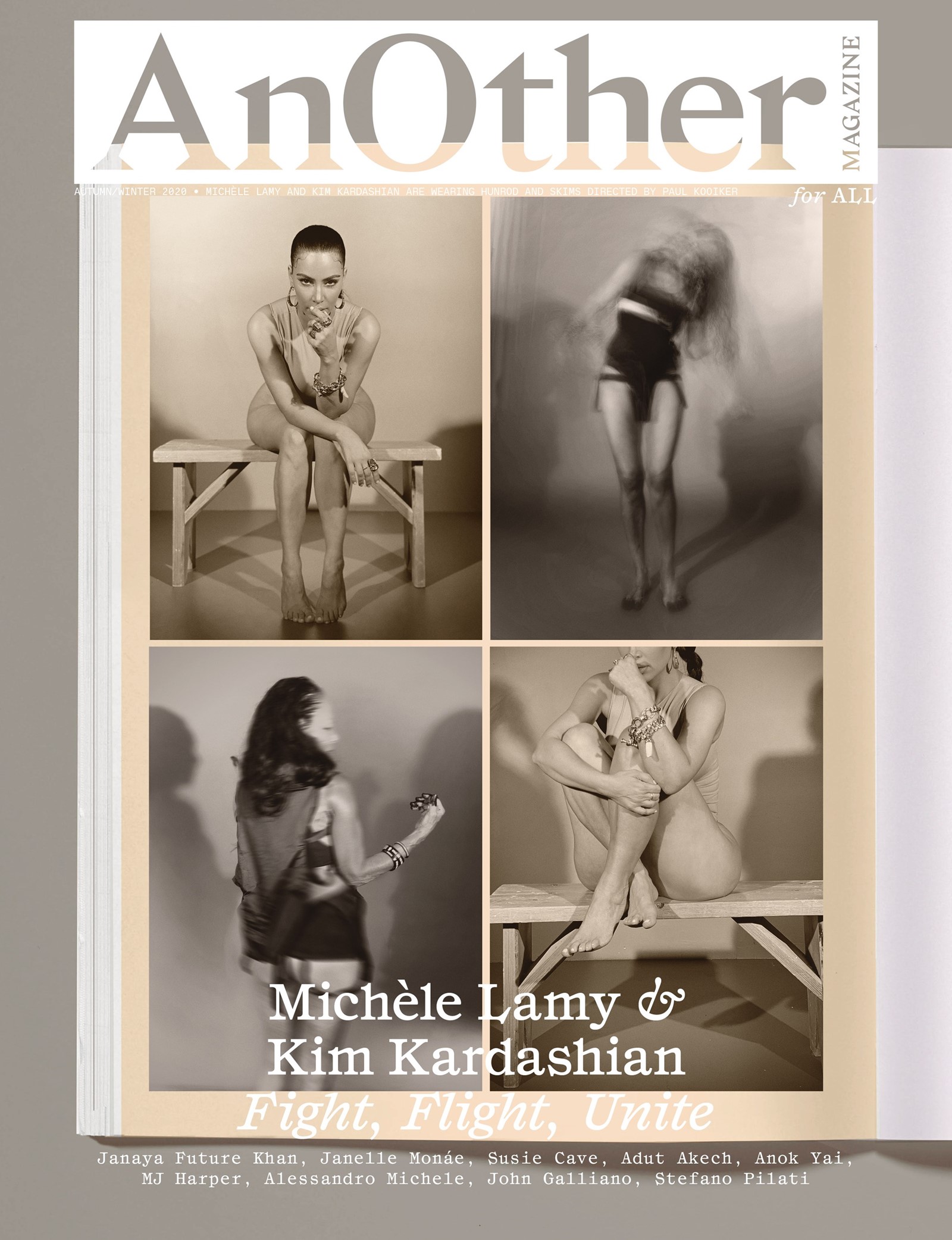

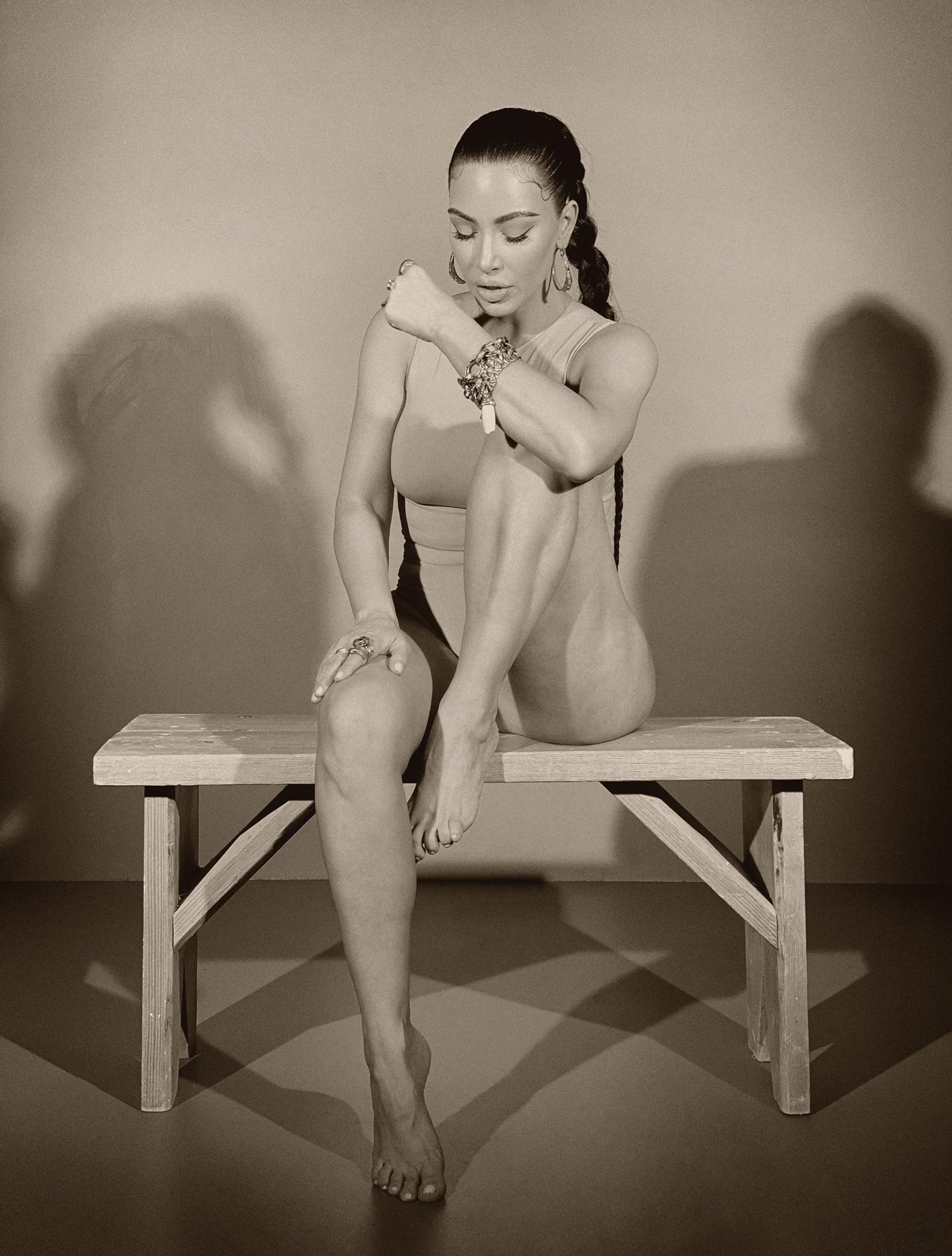

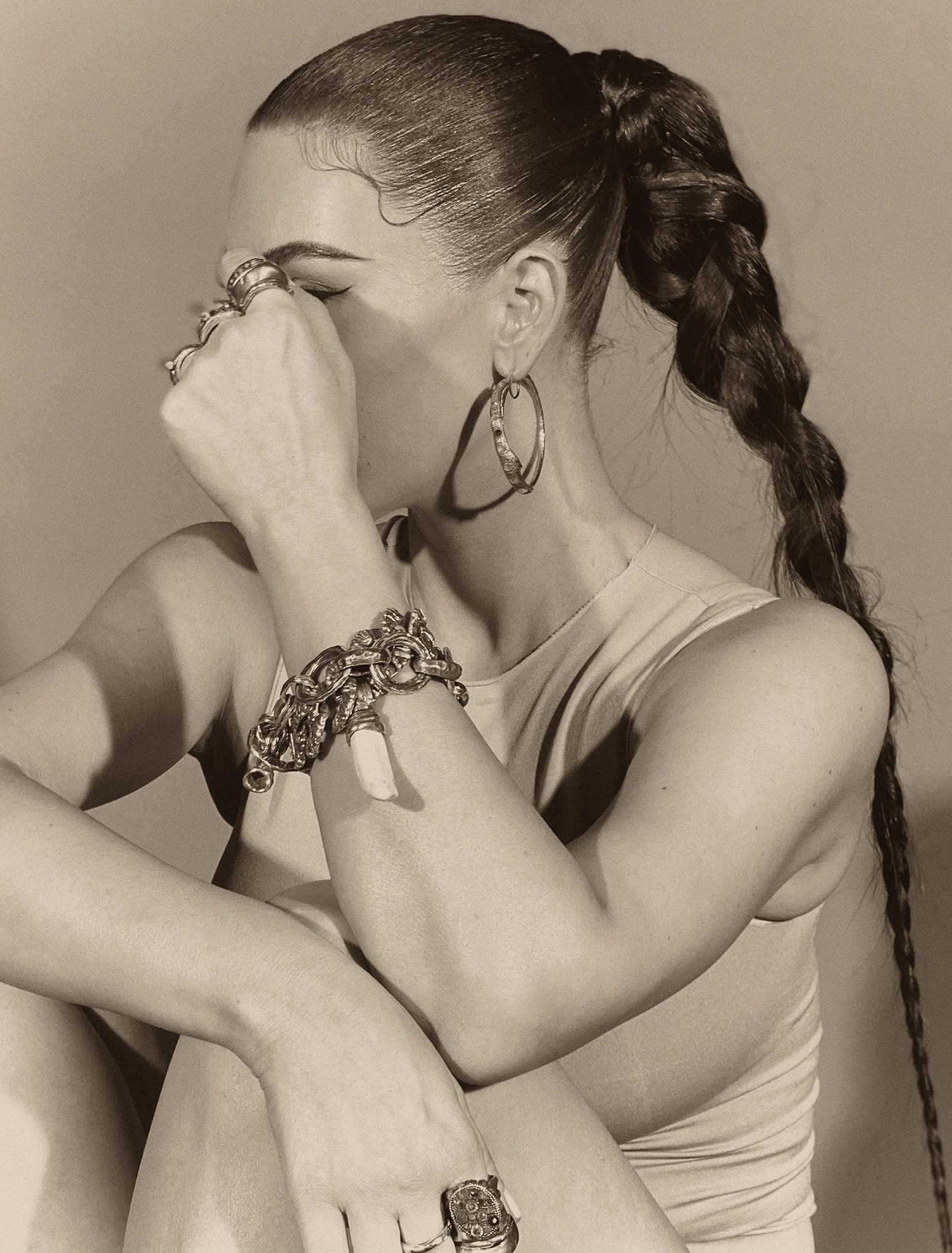

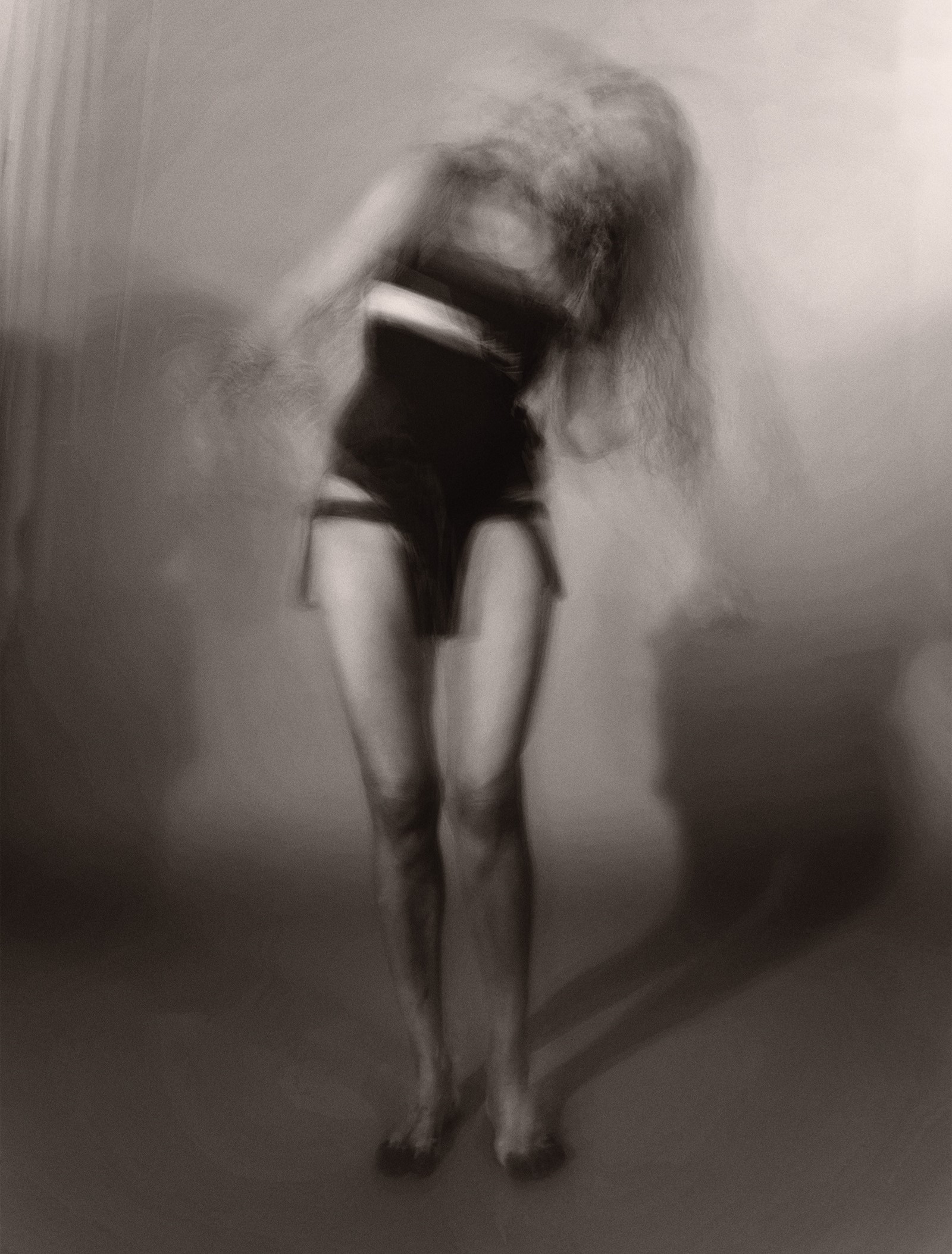

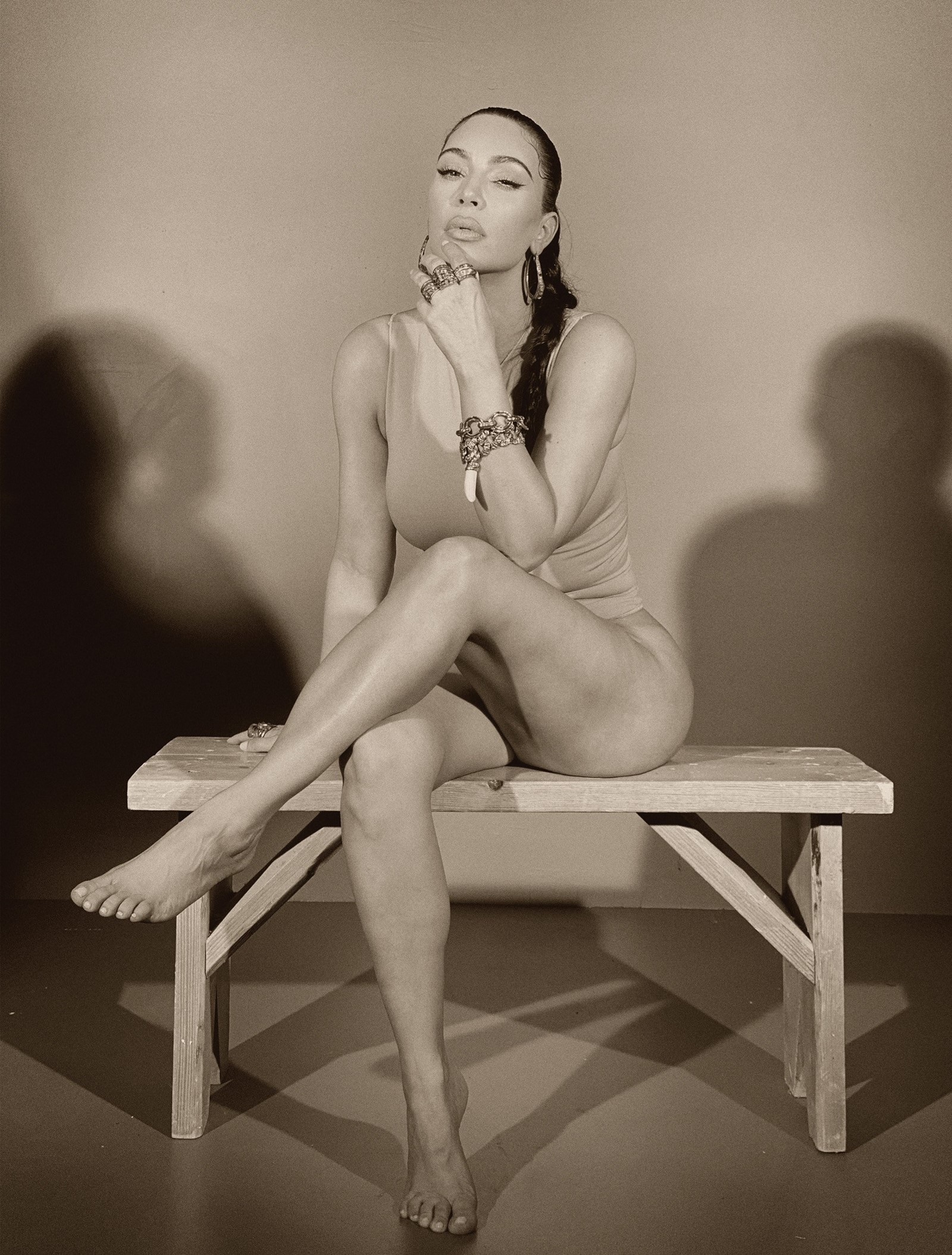

Two creative minds from very different worlds, Michèle Lamy and Kim Kardashian have formed a supportive relationship since meeting in 2013. Here, the pair are photographed wearing each other’s designs in a shoot guided by the photographer Paul Kooiker. A project conceived during lockdown – Lamy in France, Kardashian in the US, Kooiker in the Netherlands – the result is a celebration of an unexpected kinship.

From a text conversation between Michèle Lamy and Kim Kardashian, July 2020.

ML: Good morning Kim ... impatient to see us in AnOther pages ... but also looking at them I want movement, dancing, perhaps a video in the making with a song ... a duet!

KK: OMG so u think we can??? I sound awful haha

ML: So missing coming to visit you ... let’s talk, for AnOther to publish us for the sake of art. À demain, twin monkey

Kim Kardashian and Michèle Lamy’s friendship seems, on the face of it, to be an unlikely one. In June this year, the Dutch photographer Paul Kooiker gave precise instructions to both about how to shoot these portraits while they were in lockdown in their homes in Wyoming and Paris respectively. Two women in isolation, two portraits of women that could not be more different. One in a restless fit, the other pensive and venerable. Both are located in a photographic past: Kardashian’s portraits reminiscent of filmmaker Robert Bresson, Lamy’s of the photographers Bernhard and Anna Blume, all located in a time less gruesome, at a time of greatest uncertainty.

Kardashian and Lamy met in Paris seven years ago. Lamy is 11 years older than Kris Jenner, Kardashian’s mother. Lamy and Kardashian are both iconic women, albeit for very different reasons and to very different people – people who we’d assume don’t have much in common, let alone share a common sense of reality, which is what makes this relationship so interesting.

But how do we even start comprehending the complex notion of contemporary reality? My reality is very likely different to your reality – Kardashian’s different to Lamy’s, the US’s different to Europe’s, the UK’s different to Germany’s. At times, it seems we are simultaneously dealing with 7.8 billion separate realities, a world fragmented into the debris of its old order, individuals thrown back onto themselves, questioning everything that has structured and conditioned our thinking, our behaviour, everything that we thought we knew. Whatever the financial crisis of 2008 didn’t manage, Covid-19 has: it unmasked some of the ugly structures that order our world – a world that appears as a naturalised state of permanent crises. In other words, hope, hopelessness and iPhones – innovation, wealth and poverty – are all created by the very same economic conditions. As the Indian author and activist Arundhati Roy wrote so poignantly in her polemic essay The Pandemic Is a Portal, published in the Financial Times in April:

“Whatever it is, coronavirus has made the mighty kneel and brought the world to a halt like nothing else could. Our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a return to ‘normality’, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture. But the rupture exists. And in the midst of this terrible despair, it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves. Nothing could be worse than a return to normality.

“Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.

“We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.”

The virus has made visible, and thus actionable, the mechanisms that separate, humiliate, exclude and discriminate. The virus runs through all of us, it is a global connector and its fatality lines mirror those of poverty lines. Within the very same city, one hospital sees higher fatalities than another in a ‘better’ part of town; some of the most neoliberal economies, namely the US and the UK, see the highest fatalities along similar lines. How government values certain lives, or rather how it doesn’t, has never been more visible – made visible by something entirely invisible to the human eye, a virus. It should come as no surprise that Bill Gates, a software developer after all, has been warning about the risk of viruses for years. He understands the threat that a virus poses to the order of systems – the pandemic as hacker. This hack, this rupture, has already opened up some new forms of thinking, some new alliances and ways of approaching reality in the future. It helped us understand that, as the artist and theorist Ian Alan Paul states, “A pandemic isn’t a collection of viruses, but is a social relation among people, mediated by viruses.”

REALITY TV IS THE TELEVISION OF TELEVISION

Today the experience of reality, of global reality, is a mediated one. And in this process of mediation, the domain of the visual has largely replaced the textual as the dominant form through which we perceive our world, our contemporary notion of reality is enmeshed between real lived experiences and mediated realities – real-life behaviour informed by mediated realities and vice versa.

In 1973 the American anthropologist Margaret Mead wrote about a new PBS (Public Broadcasting Service) series, An American Family, in TV Guide, a rather unusual publication for Mead. This new show starred the Louds, a ‘typical’ white middle-class Californian family. “Bill and Pat Loud and their five children are neither actors nor public figures,” wrote Mead. Instead, they were the actual people they were portraying on television – “members of a real family”, which in Mead’s view constituted a new format that “may be as important for our time as were the invention of drama and the novel for earlier generations: a new way to help people understand themselves”. Nixon’s America gave rise to what Mead called “a new kind of art form”: reality TV.

In his 2011 New Yorker article The Reality Principle, Kelefa Sanneh described reality television as being “the television of television”. Less than six years later, this feedback loop intensified when a reality TV star became president and policy decisions were essentially made based on likes, retweets and ratings.

That said, reality isn’t to be confused with truth. What one perceives as real does not have also to be true. Cicero once argued that “when you say that you lie, and you say the truth, then you lie”. In The Patchwork of Minorities (1977), the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard turned this dictum around and argued, “if you say you lie, and you lie, then you are saying the truth”. He anticipated contemporary ruptures, the fragmentation of any one defining metanarrative – think king, queen, orthodox religions, a totalitarian regime, a family patriarch, a director, a white male. For him, the breakdown of any one defining metanarrative, any one proprietary relation to truth, was something liberating, something that allowed for new narrative forms, and marginal voices in particular, to insert themselves. While these observations were partly right, what Lyotard probably couldn’t have foreseen was the extent to which global capitalism would supersede these more traditional metanarratives. In many respects, what we see today in our entangled sense of reality is a conflict between competing narratives, each fighting for recognition.

Yet the success or failure of those narratives is determined by their ability to also serve economic interests, their ability to be ‘newsworthy’. Circulation, and by proxy visibility, is today largely determined by a handful of multinational news corporations that not only pursue their own financial goals but also those of their paying advertisers. Some of today’s dominant means of circulation (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram) are not owned by their users, even though they produce their ‘content’. Broadcasting services are rarely owned by the population of a country, broadsheets are not owned by their journalists or their readers. To complicate matters further, the algorithms that ‘drive engagement’ are constructed in such a way that they are, as Obama described it in his 2017 lecture at the University of Chicago, “reinforcing [one’s] own realities, to the neglect of a common reality that allows us to have a healthy debate and then try to find common ground and actually move solutions forward”. But it was also during the Obama years that social media flourished. We are still a long way from recognising the need for, and giving people equal access to, art and media education that gives them the visual literacy needed in today’s world. Only when one understands how one’s perception of reality is formed can one also change reality itself. Instead, readers or viewers have become ‘users’ and ‘followers’.

Together, the Kardashian-Jenner siblings and their mother have 774 million Instagram followers. Kim alone has 186 million (as of August 2020) – to put that in perspective, that’s more than the populations of the UK, France and Spain combined. Kim grew up with reality television and, in many ways, she is the reality TV star of reality television – a format that has come to inform and define reality itself. What makes Kim Kardashian so iconic is that she is both a result of and response to how reality is mediated, and to our relationship with it. Through her we see ourselves watching reality, and through this how we watch reality watching reality.

The rise of the Kardashian family paralleled the emergence of social media or, as Kris Jenner said in a recent joint interview with Kim at an event organised by The New York Times: “It’s important to remember that when we first got started and started filming our show back in the early 2000s, there was barely Twitter [...] Kim really was the first one in my family who taught the rest of us how to navigate that platform.” Kardashian added: “I think there was some magic of us starting on TV and really building up an audience, and then the magic of timing, of being around at the same time as social media was created. I think there was just like a hit with the TV and then another hit with social media.” In the same interview, Jenner described herself as the CEO of the family brand.

Historically, it was argued that the family performs the ideological functions of capitalism; the family acts as a unit of consumption that also teaches passive acceptance of hierarchies and norms. In the case of the Kardashians, the family itself has become a brand: “We are very mindful on our calendars to not launch a product at the same time, but if [my sister] is launching concealers and I’m launching concealers they would actually be such a different product – we have different skin and age demographics.”

In 1846, Karl Marx wrote that “at a certain state of development of the productive powers of men, you will have a corresponding form of commerce and consumption. At a certain degree of development of production, commerce and consumption, you will have a corresponding form of social constitution, a corresponding organisation of the family, of the orders or the classes, in one word, of civil society.” We are still a long way from that civil society. But, returning to Mead, it could be argued that what we are also watching is capitalism performing itself, reality TV tracing capitalism’s influence on all aspects of life and how it conditions social formations and relationships.

What makes Kardashian so unique, so iconic in the truest sense, is her self-reflexivity, her self-awareness of the medium itself and its underlining economy. Through this she also lays bare to the skin the apparatus and its mechanism and economy, probably most visible in her own brand Skims, her company for shape-enhancing undergarments. Set in liquid typography, the branding is itself an opaque word game: skims as in ’s kim’s, as in Kim’s skin, but also as in skimming, turning a quick profit, or as in reading something quickly to note the important bits only.

In April, Kardashian spoke with American social entrepreneur Van Jones about her work for the criminal justice reform group #cut50 and her plans to become a lawyer and set up her own law firm focusing on mass incarceration. Of all the possible causes that Kardashian could have focused on, she chose one of the most politically complex and contentious issues in American history: criminal justice and prison reform. “I started to educate myself and visit prisons and go and speak to people that are incarcerated and understand their backstory. It’s something I never took the time to even think about before. I met with so many people that, when they were a teenager they committed horrific crimes, but now in their thirties, forties, they are a completely different, rehabilitated person, and even though they did that and made that choice and mistake to do something really awful, it does not mean they are that mistake.” She doesn’t claim to be Angela Davis – in fact, for many, #cut50 does not go far enough – but what Kardashian does understand very well is what it means to be portrayed as a mistake and what it means to be locked into an image.

Lamy, by contrast, has much more of an archaic image. She’s an icon of a different epoch, as much an enigma as she is an impresario. Her look can be described as part north-Moroccan Berber, part Kinski in Herzog’s Nosferatu, part Richard Kiel as Jaws in the James Bond films and part Romy Schneider.

Her biography reads like something from a French nouvelle vague script: could be Algerian, maybe Swiss, maybe French; studied with Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze in 1960s Paris, and worked with them at La Borde, an experimental psychiatric clinic where Deleuze and Guattari developed their theory and practice of schizo-analysis; studied politics and law; was a defence lawyer; lived in Los Angeles, of which she has said: “LA is the only place where people have five vodka martinis, but say they can’t eat the carrots because of the sugar.” There, she ran two renowned restaurants in the 1990s – Café des Artistes and Les Deux Cafés – both part 1950s Hollywood hangout, part 1920s Weimar Republic cabaret.

Under the name Lamyland she creates IRL platforms, settings for people to engage with the eclectic mix of her collaborators, from the Bronx-based culinary collective Ghetto Gastro, to her boxing friends at the New York club Overthrow, to A$AP Rocky, to her own band Lavascar. In her recent quarantine Instagram TV series What Are We Fighting For?, she interviewed artists, musicians, curators and computer-game developers, idiosyncratic facilitators of change. Lamy’s restlessness seems to be searching for a way out of our contemporary predicament. Like the maverick she is, Lamy does not seem to be bothered to do right or even be virtuous. She rejects all orthodoxies; not only do they seem to bore her, but for her, learning happens on the cusp of the imaginable. Welcome to Lamyland, a land without territory, borders or followers – a territory as a state of mind. When asked in a recent interview whether she was attracted to extremes, she replied: “For me it is people that want to win, that want to be bored, this is what is for me extreme.”

It is Lamy’s curious fearlessness, her shamelessness in the true sense of the word, that makes encounters like the one between Kardashian and herself possible, cutting through a reality defined by algorithms, clichés, biases and ready-made ideas of a world where everything and everyone has an assigned proper place.

Our notion of reality is enmeshed with our mediated one, and it’s a very messy affair rife with antagonisms. Yet working through this mess is the only option we have for creating new narratives as well as new forms of production, not only towards more-just forms of representation but also towards more-just means of producing reality itself.

This story appears in AnOther Magazine Autumn/Winter 2020, which is on sale internationally from October 1, 2020.